Upoma Dutta (MBA ’21) talks with Netflix co-founder Marc Randolph about his new book and the venture that most thought would never work.

How often have you tried to explain a direct-to-consumer subscription model created by HBS alumni, and decided you were better off just calling it “the Netflix of … something?”

Rent the Runway—“the Netflix of Fashion.”

Peloton—“the Netflix of Fitness.”

Birchbox—“the Netflix of Cosmetics.”

With more than 150 million subscribers, Netflix is arguably the world’s most popular subscription service. More importantly, it changed the course of the global media and entertainment industry over the last 15 years, as it pivoted from DVDs to online streaming, and then from predominantly licensed content to predominantly original content.

Could its founders have envisioned that this “new media” venture—with its humble roots in the unproven online DVD rental space—would go on to disrupt a multibillion-dollar industry?

“No, never in a million years,” Marc Randolph, Netflix’s co-founder and former CEO, tells me in our recent conversation. “Look at the twists and turns that Netflix has taken. If people say they could predict the outcome that Netflix has achieved, it’s magic or lying.”

Company founders are notorious for having hindsight bias. They often attribute the origins of their venture to make-or-break “epiphanies,” the lightbulb moments that led them to connect the dots between market needs and new products.

Similarly, I had expected Randolph to talk about the eureka moment that led him to start Netflix and about how he and his co-founder Reed Hastings could foresee the disruption that the Internet would foist on the media and entertainment industry.

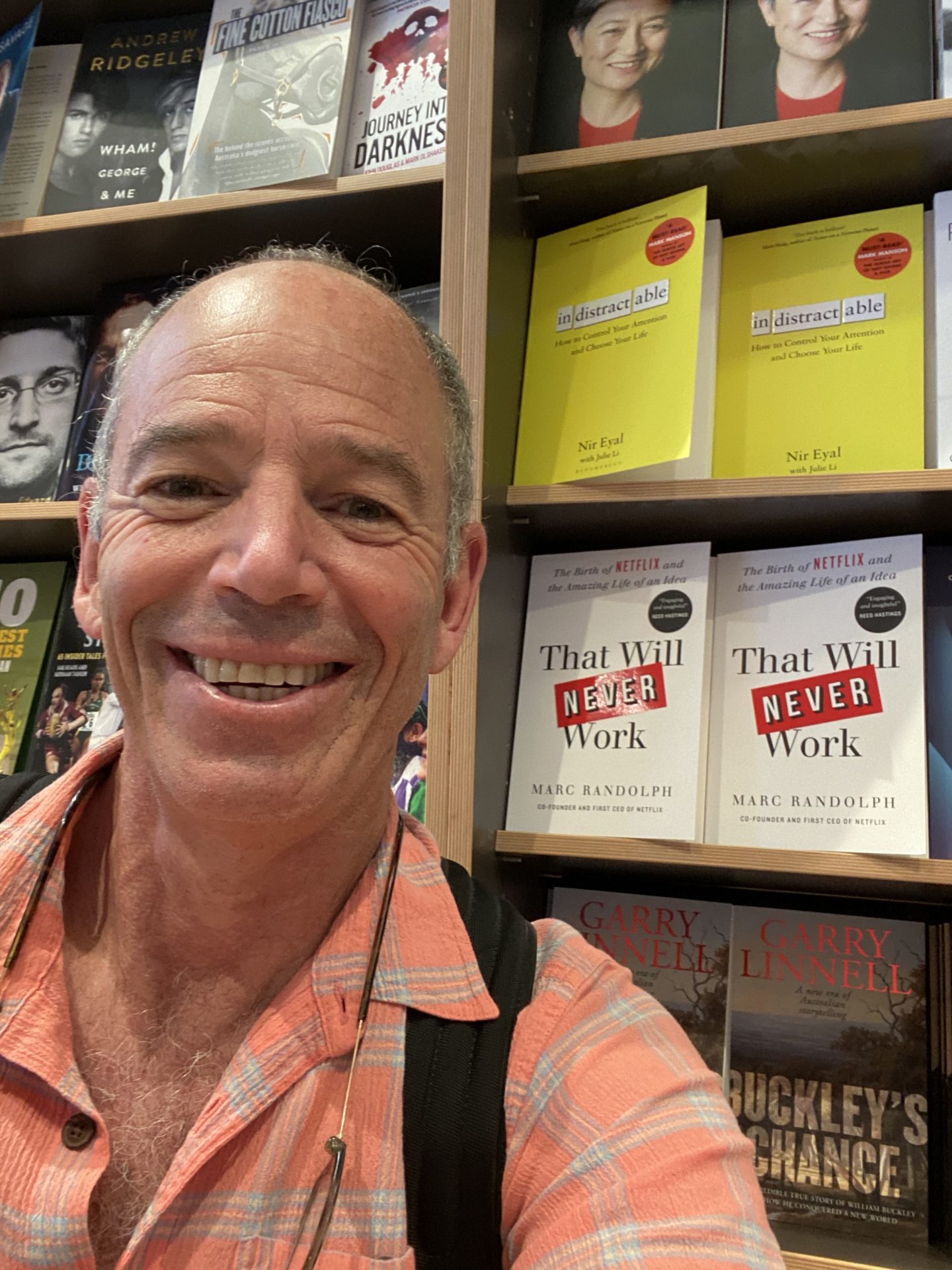

Instead, his “nobody-knows-anything” admission surprised me. It’s the same unassuming candor that makes Randolph’s new book That Will Never Work a delightful and insightful read, especially for budding entrepreneurs.

In the book, Randolph describes the many carpools he shared with Hastings, now the current CEO of Netflix, in the late 1990s. Hastings was in the process of selling off the company in which Randolph also worked, which meant that both would be out of jobs soon. Hence, the rides presented the perfect opportunity for Randolph to bounce business ideas off Hastings.

But the “best idea” was hard to come by, especially since Randolph’s area of search was as wide as “selling things on the internet.”

Personalized shampoo, personalized surfboards and even personalized dog food were among the 100-plus ideas that Randolph considered, but they were shot down in the exchange with Hastings. Randolph also lets out a secret: all these ideas once seemed better than the idea of online DVD rentals that Randolph and Hastings would eventually settle on.

Randolph’s revelation on the origins of Netflix likely holds two powerful lessons for entrepreneurs. First, execution could be more important than the initial idea itself. Second, once you settle down on an idea, don’t let the voices of skeptics dissuade you from turning the idea into reality.

For instance, one of the early venture capitalists to whom Randolph and Hastings pitched the idea of Netflix shot it down, saying it was “sh*t” as he predicted that DVDs would soon become obsolete and studios would move to either downloading or streaming. But the Netflix co-founders still moved on.

“Even though we recognized that he was right about media eventually moving to downloading or streaming, we did not agree with his time horizon,” Randolph explains. “We believed that the move to digital would not start for many, many years and that full market adoption of the digital format would take even longer. In fact, the real streaming wars started only recently, almost 22 years after Netflix launched.”

However, Randolph was careful not to position the company as a “DVD business.”

“We were always agnostic of the delivery mechanism,” Randolph says. “We built a business and positioned it in such a way that all our efforts to make the DVD business work would be assets that we could carry forward for the streaming business. For instance, from the beginning, we let consumers rate movies. From the beginning, we invested in building algorithms to predict what consumers would want to watch. That was the clever part.”

Once Netflix launched, operating a business in the still-nascent e-commerce space presented its own share of unique challenges (such as multiple launch-day server crashes). Negotiating deals as a David with too many Goliaths in the industry (such as movie studios and DVD player manufacturers) would prove to be equally challenging.

“It was often frustrating. Nobody would take you seriously. You would spend 80% of your time not on convincing others of the merits of your idea but on convincing them why they should pay attention to you in the first place.”

Netflix’s initial lack of credibility was clearly apparent when the company tried to sell itself, twice—once to Amazon and once to Blockbuster. Both deals fell apart, as Amazon valued Netflix at “low eight figures” while Blockbuster CEO “struggled not to laugh” at Netflix’s asking price of $50 million.

Now, in hindsight, not being taken seriously was likely a blessing in disguise, as Netflix continued to reinvent its business model, with each strategic pivot helping it to increase its market value. (Netflix now has a market cap close to $140 billion—note the “b.”)

Along the way, Netflix co-founders learned about two important ingredients for scaling a company: ruthless focus and consumer-centricity.

“Focus is paramount when growing a business,” Randolph elaborates. “An organization has limited bandwidth, and you have to decide where to put your smart people. Many companies would put their people on two initiatives, and then each initiative becomes under-resourced. This is a big mistake, as each initiative would face a competitor that has gone all-in.”

Case in point: in the first year, Netflix ditched the only part of the business that was bringing in revenue (DVD sales) so that it could focus singularly on building a recurring consumer base through DVD rentals (and later, subscriptions).

Second, putting consumers front and center has always been a big part of Netflix’s culture.

“At Netflix, from the very beginning, nobody’s opinion mattered but consumers’. But we did not pay attention to what consumers ‘said’ they wanted. Instead, we built sophisticated ways to understand what consumers wanted based on their actions.”

Netflix’s rigorous A/B testing culture likely traces its roots to this earlier data-driven consumer orientation.

Randolph left Netflix shortly after the company went public in 2002. Asked if it was difficult parting from a company that started as his brainchild, Randolph displays a strong sense of self-awareness.

“I knew I did not enjoy being a late-stage, big-company CEO. From a young age, I learned that what I liked and what I was good at was the same thing—startups in really early stages.

“To me, being successful is not owning a big house or a fancy car. Instead, it is being able to do things that you like and that you are good at.”

Randolph would go on to co-found other business ventures, such as Looker (an analytics startup that Google decided to acquire for $2.6 billion early this year).

We ended our conversation with his advice to young would-be entrepreneurs, based on his multi-decade experience in leading startups.

“If you want to be an entrepreneur, you should start a venture as soon as you can. Working in startups is really hard, something you might not learn within the confines of the classroom. So, my advice is, just do it.”

Upoma Dutta (MBA ’21) came to HBS after spending roughly four years in the media and entertainment industry in New York, where she helped two media companies (HBO and Disney) transition into the streaming era and build on new strategic growth opportunities. Originally from Bangladesh, she also worked for the International Finance Corporation (World Bank Group) early in her career to promote financial inclusion and financial sector stability in South Asia. She holds a bachelor’s degree in business administration from The Institute of Business Administration, University of Dhaka.